Qualitative analysis of Host Cell Proteins using mass spectrometry

Analytics, Drug development, Drug product, Drug substance

- Host Cell Proteins (HCPs) are process-related impurities, that are co-produced with the desired product during biologics manufacturing and have significant impact on its quality and stability. Careful monitoring and effective removal of HCPs are critical to ensure biologics safety and effectiveness.

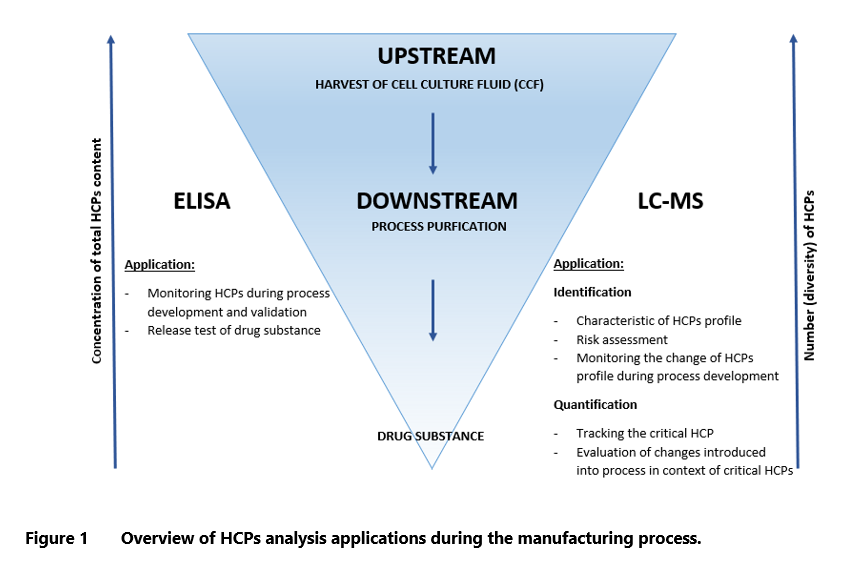

- The development of LC-MS/MS technology has enabled mass spectrometry-based methods to serve as orthogonal approaches for HCPs determination. This technology identifies proteins in HCPs pool and allows for quantification of critical HCPs. It helps to understand the impurities profile, identify potentially problematic proteins and simplifies risk assessment.

- The strategy for MS analysis should be aligned with the defined purpose. Some approaches are superior for qualitative characterization of total HCPs, while others are designed for identification or quantification of specific protein species.

Host Cell Proteins in biotherapeutics

Technology of biopharmaceuticals production has advanced rapidly over the last fifty years. The production of protein-based biotherapeutics uses various prokaryotic and eukaryotic expression systems such as Escherichia coli (E. coli), yeast (Saccharomyces cerevisiae, Pichia pastoris), human (HEK-293) and animal cell lines (CHO DG44, CHO DUKX-B11).1,2 Regardless of the used system, biopharmaceutical companies must face the problem of impurities, which may contaminate the product throughout the different manufacturing stages. Regulatory agencies (EMA, FDA) classify such impurities into two categories: product-related (e.g. degraded product forms) and process-related. Process-related impurities include three groups according to their source: cell substrate-derived (e.g. host cell proteins, host cell DNA), cell culture-derived (e.g. medium components) and downstream-derived (e.g. reagents, solvents, ligands).

Host cell proteins (HCPs) are a significant class of the process-related impurities that are expressed by host cells during the upstream process and coproduced with the desired product.3 As a result, the raw cell harvest contains a mixture of undesired host-derived proteins with various physicochemical and biochemical properties, sizes (approximately, from 5 kDa to 250 kDa), concentration and content (dependent on the purification stage). The HCP profile is unique and specific to individual cell cultures, depending on culture conditions and production processes.1,3

Impact on the product

The HCPs in biopharmaceuticals are considered as a critical quality attribute (CQA) due to their potential impact on product’s quality and stability, and in consequence, efficacy and safety for the patients.1 The risk from Host Cell Proteins impurities may be mediated by their detrimental effect on immunogenicity or biological activity. Even trace amounts of immunogenic HCPs may cause safety issues, such as allergic reactions or development of anti-drug antibodies that can reduce therapeutic efficacy of the product. The risks associated with HCPs presence include also their potential biological activity. The Host Cell Proteins with protease, glycosidase, or lipase activity can lead to degradation of therapeutic proteins, compromising their quality and reducing product’s shelf life and potency.4,5 In the history of biopharmaceuticals, there have been several examples where the final products contained HCPs impurities at levels high enough to raise safety concerns. Most of these impurities were discovered during the clinical development and had to be removed by introducing changes to the manufacturing process. For example, phospholipase-B–like 2 (PLBL2) produced by CHO cells went undetected by a platform ELISA during the late-stage clinical trials of lebrikizumab, resulting in untoward immune responses and delaying the trials’ completion as well as regulatory submissions. Another incident concerned CTLA4-Ig molecule, where contamination with monocyte chemoattractant protein (MCP-1) induced acute toxicities and resulted in phase 2 study being put on hold (CTLA4 is a fusion protein of the immunoglobulin Fc region with Cytotoxic T-Lymphocyte Associated Antigen).4,6

Requirements of regulatory agencies

Regulatory agencies such as FDA and EMA require thorough characterization and quantification of residual HCPs as a part of product release and approval processes. However, the regulatory guidance on HCP impurities is limited to recommending that the product be as pure as practically possible, without specifying a numerical limit. The accepted level of HCPs in the final product is evaluated on a case-by-case basis, because the risk associated with HCPs presence often depends on multiple clinical factors (incl. route of administration, dose, indication and patient population) as well as the specific impurity.4,7,10 As stipulated in the EMA guideline:

“Potential process-related impurities (e.g. HCP, host cell DNA, cell culture residues, downstream processing residues) should be identified, and evaluated qualitatively and/or quantitatively, as appropriate”.7

At the same time, Host Cell Proteinsdetection methods can be used to control the manufacturing process and to monitor the effectiveness of purification procedures at various stages of production. Development of such method is a major step to establishing efficient control of contamination during the process development, manufacturing, and quality control of the final biopharmaceutical product. Most HCPs acceptance levels cited in the contemporary literature fall within the range of 1 to 100 ppm (1–100 ng/mg of product).5,8

Host Cell Proteins Detection Methods

Efficient reduction of Host Cell Proteins impurities is crucial for patients’ safety and successful drug approval. Appropriate detection and measurement techniques should be developed already by the early stage of clinical development.4 Several analytical approaches have been established for that purpose, of which the most important are: two-dimensional sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (2D SDS-PAGE), western blot, immunoassay and LC-MS method.8-10

ELISA as the gold standard

For decades, immunoassays in the form of sandwich enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA), have been used as the gold standard for controlling the level of HCPs in biopharmaceutical products. Host Cell Proteins ELISA is a multi-analyte immunoassay that uses polyclonal antibodies generated via animal immunization with the use of a null cell line (production cells deprived of the product-coding genes). This method gained much popularity owing to its several advantages, such as high sensitivity, specificity, wide dynamic range, high throughput, possibility of automation and quantitative nature. ELISA is a reagent-dependent assay, where the quality of polyclonal antibody and HCP antigen used as an assay standard is of critical importance.

One of the main limitations of ELISA is that it doesn’t detect HCPs that are nonimmunogenic or weakly immunogenic to animals used for antibodies production. Additionally, it may underestimate or overestimate levels of Host Cell Proteins. Excessive amounts of highly immunogenic antibodies may distort the result for other antibodies or, conversely, the assay can be compromised by insufficient amount of detection antibodies.

ELISA results are expressed as total HCPs content in nanogram of HCPs per milligram of drug substance (ng/mg or ppm). This method does not provide information about identity or quantity of individual Host Cell Proteins.1,10-12.

Introduction of orthogonal methods

Awareness of Host Cell Proteins ELISA limitations and rapid development of analytical technologies in other areas, e.g. proteomics, have highlighted the need for orthogonal methods to support the assessment of product’s quality and safety. Moreover, cases of delayed or rejected clinical trial applications due to inadequate monitoring of HCPs have caused regulatory authorities to routinely request orthogonal HCPs data, shifting the focus from total HCPs levels to individual HCP quantification.1,4

In 2020, United States Pharmacopeia (USP) convened an expert panel of industry, academic, and regulatory specialists to address the best practices for HCP analysis by MS. This endeavor resulted in the release of General Chapter <1132.1> “Residual Host Cell Protein Measurement in Biopharmaceuticals by Mass Spectrometry” in December 2024, which will become official on May 1, 2025. In the sections below, we provide a brief review of standardized techniques used in MS-based HCP analyses.1,13,14

LC-MS as an orthogonal method

The technology of liquid chromatography coupled with tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) provides alternative solution for HCPs analysis. The major advantage of MS over more traditional techniques is that it allows to identify and quantify individual proteins in HCPs pools. There is a significant difference if 100 ng/mg of the total Host Cell Proteins amount (as determined with ELISA) constitutes one protein present at 100 ng/mg concentration or a hundred proteins, each in the amount of ~1 ng/mg. Additionally, identification of individual Host Cell Proteins enables the assessment of their impact on drug’s safety. This exercise builds an understanding of HCPs, simplifies risk assessment and allows to pin down the potentially problematic protein species. Consequently, it is possible to design the targeted purification strategy for specific HCPs and monitor that process. In contrast to ELISA, MS methods are not dependent on critical reagents and long process of immunization, resulting in shorter method’s development time for a new product utilizing the same expression system.1,5,12

Nevertheless, MS-based techniques are not free from limitations. The biggest challenge in the identification of HCPs by MS is the dynamic range limitation of MS detection. In highly purified samples, like drug substance, impurities are reported at ppm levels, meaning that the level of product peptides is 106 times higher than that of HCPs peptides. In such a situation, detection of 10 to 1 ppm of individual HCPs requires a dynamic range of 5 to 6 orders of magnitude. Currently the highest dynamic ranges reported by MS vendors oscillate around 105. The goal of most HCP analyses is to obtain the required ppm detection levels. To overcome this limitation, one can use enrichment or depletion strategies that reduce the amount of product proteins or optimize the overloads of column and/or parameters of the MS system. The throughput of MS method is relatively low, because of the time-consuming and complex processes of sample preparation, instrument acquisition as well as analysis and interpretation of large datasets. Sample preparation process consists of multiple steps, each posing a risk of HCPs loss. Additionally, the sheer number of variables that may be introduced during the sample preparation, chromatographic separation, data acquisition and analysis, may cause challenges in obtaining reliable and reproducible results. On the top of that, introduction and maintenance of LC-MS method requires high investments in appropriate device and software, along with employment of experienced analysts who are well trained in MS data analysis and interpretation. Adaptation of established method to the cGMP requirements also poses a significant challenge.1.

Principles of the LC-MS method

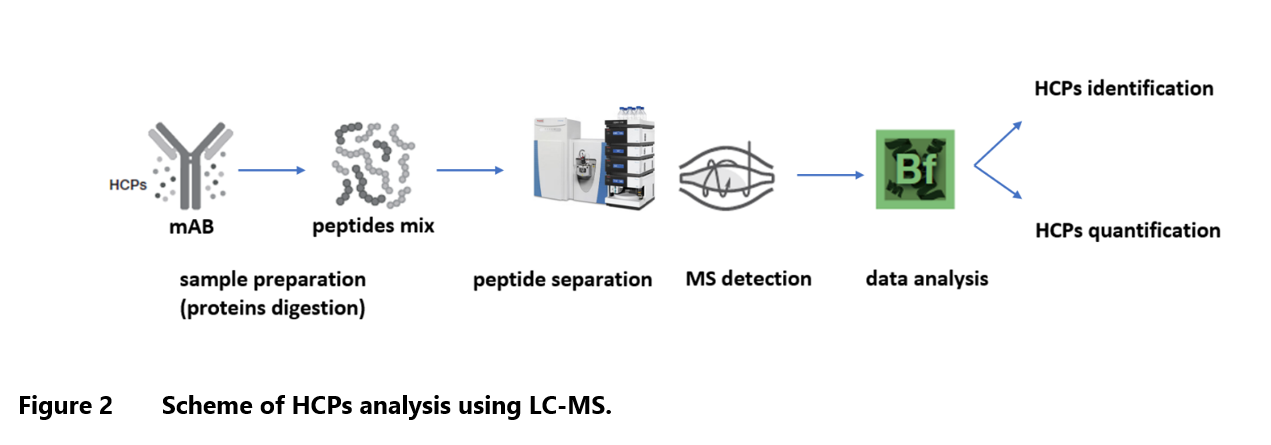

The LC-MS method of HCP identification involves peptide sequencing technique (peptide mapping), based on proteomic bottom-up approach. In general, it consists of enzymatic digestion of protein, followed by chromatographic separation and tandem mass spectrometry analysis. The amino acid sequences are confirmed by comparison of experimental MS2 mass spectra of peptide fragments with their theoretical mass spectra deposited in database. Various samples of HCPs may differ by molecular size of proteins, its properties and concentration, all of which may have significant impact on each step of analysis.

The LC-MS analysis can be divided into a few main steps: sample preparation, peptides separation by liquid chromatography, MS/MS detection (to fragment the separated peptides for sequence information), data processing and analysis (to identify peptides and map HCPs from protein sequence database) (Figure 2). Most published methods developed for HCPs identification are designed for monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) and they require adaptation to the other biotherapeutics appearing on the market, such as mAb-related proteins, e.g., bispecific antibodies, antibody drug conjugates (ADCs), Fc-fusion proteins and other biopharmaceuticals including vaccines, cellular- and tissue-based products, and biocatalysis products.1,14-16

Sample preparation

Standard bottom-up approach consists of the following main steps: buffer exchange, protein denaturation, reduction, and alkylation, and finally proteolytic digestion. Many excipients present in drug formulations, such as detergents, polymers and high concentrated salts, may have negative impact on sample solubility, digestion efficiency or alkylation completeness. They can also cause interference or introduce high background signals in the mass spectra.

Buffer exchange may be necessary when the method is used to compare samples with widely different formulations, e.g. samples from different stages of the manufacturing process. There are many techniques that allow for elimination of unwanted buffer components during sample preparation, including dialysis, ultrafiltration, solvent precipitation of protein or detergent removal columns. It is crucial to understand that sample processing method can influence the recovery of individual HCPs. For instance, desalting columns or diafiltration techniques with a molecular weight cut-off may eliminate certain lower-weight HCPs from a sample.

The most common method of peptide mapping includes the steps of denaturation, reduction, and alkylation, which result in equal efficiency of subsequent digestion reactions for both product and HCPs. For denaturation step, usually chaotropic agents, such as guanidine hydrochloride or urea, are used. Disulfide bonds are first reduced using reducing agents such as tris(2-carboxyethyl) phosphine (TCEP) or dithiothreitol (DTT). The resulting “free” cysteines are alkylated with the use of reagents such as iodoacetamide or iodoacetic acid. Next, the denatured, reduced and alkylated proteins are subjected to digestion. Although there are many specific proteases available on the market, the most popular is trypsin, primarily due to its high specificity and unlimited commercial supply. Moreover, by cutting polypeptide chains right after arginine and lysine residues, trypsin creates positive charges at C-terminal ends of the obtained peptides, thereby improving ionization in the mass spectrometer. Nevertheless, the selection of right enzyme must always take into account the specific properties of the targeted proteins. During method development, factors such as protein-to-enzyme ratio, digestion duration, temperature and pH of digestion, should be optimized. The specificity of digestion can be evaluated by analyzing the number of peptides with missed cleavage sites. It is worth mentioning that samples with drug substance are highly purified and contain a million times more desired protein than individual HCPs, which may complicate chromatographic separation (column overloading) and MS detection (dynamic range limitations of the instrument). As a consequence, standard bottom-up method may not be sufficient to detect HCPs of very low abundance, making a modified approach necessary.1

Several techniques for improving method sensitivity are available, including depletion of DS protein and enrichment of HCPs. Depletion can be readily achieved with the use of affinity chromatography. The column that binds the product protein (e.g. protein A affinity column for monoclonal antibodies) allows to obtain the purified fraction of HCPs in flow through. Unfortunately, this approach does not allow to detect HCPs bound with the product by coadsorption (hitch-hikers). The next technique is separation of the desired protein and HCPs by a molecular weight cut-off (MWCO) filter. In this technique, the larger DS proteins are retained on the filter, while HCP fraction, which typically consists of smaller molecules, can be collected in a flow through. The obvious disadvantage is that any HCP with a molecular weight higher than the cutoff will be retained together with the DS. When the desired protein has distinct physicochemical properties (e.g., size, charge or hydrophobicity) compared to most HCPs, LC-based fractionation can be applied instead. Methods such as hydrophilic interaction liquid chromatography (HILIC), size exclusion chromatography (SEC) or reversed phase liquid chromatography (RP-LC) can be selected based on specific properties of the DS. Similarly to the affinity chromatography, hitch-hiker HCPs will be missed during LC fractionation due to coadsorption to the product proteins.

Another strategy of protein product depletion is based on modification of the digestion conditions. The next example is a method where all proteins are digested under native conditions without denaturation, reduction and alkylation step that is present in the standard technique. This approach is dedicated mostly to monoclonal antibodies and antibody-related products, which are relatively resistant to trypsin digestion in their native state. Undigested antibodies can be precipitated using heat treatment or membrane filter, leaving HCPs peptides in solution.1,17 However, with this technique there is a risk of losing some HCPs that are resilient to digestion under native conditions. It should be noted that the methods based on DS depletion and/or the enrichment of HCPs pose challenges when it comes to the quantitative determination of nanograms of HCP per milligram of product protein, as they unavoidably affect the concentration of the detected proteins. 1,18

Host Cell Proteins can also be directly enriched by affinity chromatography. One of the solutions is to use polyclonal anti-HCP antibodies (e.g. the same as used in HCP ELISA) immobilized on affinity column or beads. However, the key problem with this method is that the employed polyclonal mixture may be missing antibodies against some HCPs. The alternative approach is to use affinity separation beads coated with ligands specific for the individual HCPs. These ligands are derived from a combinatorial library of peptides or aptamers that in theory are capable of binding the particular HCPs. The downside of this approach is the inherent difficulty in predicting and assessing specificity of HCP-ligand binding.1

Importantly, every step of sample preparation carries the risk of HCPs loss. For instance, using filters with the defined molecular weight cut-off may miss some HCPs with lower or higher molecular weight (depending on the target fraction) or digestion efficiency may differ from the one predicted for HCPs and product protein. In general, the less the sample is manipulated, the greater the likelihood of detecting HCPs. However, in cases where the analysed HCPs are at very low levels e.g., when enzymatic activity on the product is observed but HCPs are not detected in the standard bottom-up approach, it may be worthwhile to introduce an additional step into the sample preparation procedure. Although this extra step may lower quantitative accuracy of the total HCP detection compared to the standard bottom-up approach, reduction of the DS protein and targeting HCPs within the dynamic range of device can improve the sensitivity of analysis.1

Chromatographic separation

After sample preparation, the obtained peptides are separated by liquid chromatography (LC) and then passed to mass spectrometer (MS). During the development of separation process, it is important to remember that LC and MS work together. The biggest challenge during the optimization is finding a compromise between loading a high amount of digested protein and not overloading the column. The purpose of loading a substantial portion of protein is to maximize low-abundance HCPs detection. However, this can lead to the suppression of ionization of coeluting HCP peptides, saturation of the MS detector response and/or increase in the complexity of MS/MS spectra.

The main parameters that can be optimized during the development of separation method are type of phase, gradient program, flow rate, oven temperature, type of column and injection amount. The gradient should be adjusted to the analysed peptides. For example, in case of drug substance sample with low-abundance HCPs, slower and/or shallower gradients may improve separation between analytes. But in this case, the throughput will be lower than for faster gradients. Also, lower flow rates, such as nano-flow or capillary flow, can improve sensitivity with a simultaneous reduction in the amount of loaded sample. In general, higher temperatures promote better mass transfer characteristics and sharper elution peaks.

The most frequently used column in bottom-up analyses is a reversed-phase C18 column. Its size, loading capacities, selectivity, and resolving power should be determined experimentally. Longer columns and two-dimensional liquid chromatography (2D-LC) can improve HCP detection, although 2D-LC is less commonly used due to its lower throughput. Optimized chromatographic separation should ensure reproducibility between injections and between days. Finally, the cleaning strategy should be applied to prevent carryover effect.1

Host Cell Proteins MS analysis

The analysis of HCPs with the use of MS technology requires a tandem mass spectrometry (MS/MS or MS2), which enables ions fragmentation. In standard proteomic MS/MS analysis, peptides separated during the liquid chromatography are ionized and introduced into the mass spectrometer. The first mass analyzer separates ions by their mass-to-charge ratio (m/z) – it is a first scan event. Ions of individual m/z values (precursor ions) are selected and then subjected to collision activation, where product ions of different m/z values are created via fragmentation. These fragments are then introduced into the second mass analyzer, which allows for their separation and detection (second scan event). The obtained data are searched by software algorithms to identify the peptides and the proteins from which they originate.15

Due to the rapid technological advancements, many types of instruments for MS analysis became available on the market. In proteomic analyses, the electrospray ionization (ESI) is the most common type. As a soft ionization instrument, it overcomes the susceptibility of macromolecules to fragmentation during the ionization process. The most popular fragmentation technologies in HCPs analyses are collision-induced dissociation (CID) or higher energy collisional dissociation (HCD), but alternative fragmentation modes are also possible (e.g. electron-transfer dissociation (ETD) or surface-induced dissociation (SID)). Mass analyzer and detector may be selected depending on the analytical purpose, including information about sample type, acquisition mode, device’s resolution and accuracy. By reviewing the literature, it can be seen that the most commonly used configurations of the mass analyzers in MS/MS are: triple quadrupole (QQQ), quadrupole-time of flight (Q-TOF), and quadrupole-Orbitrap (Q-Orbitrap).1

Two different strategies of MS-based protein analysis can be distinguished: untargeted and targeted. As suggested by its name, the objective of untargeted strategy is to discover unknown proteins of interest. It can be based on one of two acquisition modes: data-dependent acquisition (DDA) or data-independent acquisition (DIA). In DDA, peptides with higher intensities at a given chromatographic elution time are selected for fragmentation and subsequently identified through a protein database search. The software starts with the most intense precursor ions and applies dynamic exclusion to avoid previously fragmented masses, allowing for the collection of data on lower-abundance ions. The advantages of DDA are its high specificity and easier data interpretation, as the small m/z window results in MS/MS spectra specific for the individual peptides. However, the chief limitation is that not all precursor ions can be selected due to the instrument’s speed and peptide elution times, which may result in low-abundance HCP peptides being missed. Also, precursor selection may vary between the injections, leading to inconsistent detection of low abundant peptides in replicate injections. In DIA, all precursor ions present at a given retention time and/or within an m/z window are simultaneously selected for fragmentation. The advantage of this mode is that MS/MS data are continuously collected for all components in the sample, without applying any precursor selection criteria. However, the resulting MS/MS spectra can be complex, and interference from coeluting peptides may impede the confident identification of peptides and HCPs.

A fine example of an untargeted strategy is the SWATH technology, which has a data-independent acquisition mode. In SWATH, the mass range is partitioned into small mass windows, and then analyzed using tandem MS. The windows are stepped across the mass range on LC timescale, transmitting groups of analytes for fragmentation and generating MS/MS spectra at each step. The window width, the number of windows and accumulation time per window can be adjusted based on the density of analyte precursor masses eluting from the column. The narrower the isolation window, the better the signal/noise ratio, but it must be balanced by the size of range of masses that needs to be explored.1,12,15,16,19

The targeted strategy requires information about the proteins of interest. In this approach, instrument searches and selects only manually defined m/z precursors for predetermined peptides. In the next step, peptides are fragmented in a collision cell, and fragment ions are directed to the second mass analyzer and detector. The superiority of the targeted approach rests on its higher reproducibility and sensitivity. Three types of the targeted strategy are usually distinguished in the literature: selected reaction monitoring (SRM), multiple reaction monitoring (MRM) and parallel reaction monitoring (PRM). In MRM and SRM analysis, only one fragment ion at a time is sent to the detector. In contrast, during PRM analysis, all fragment ions from the defined precursor are scanned by the second mass analyzer before reaching the detector. These methods improve quantification accuracy and enhance the dynamic range. However, in MRM and SRM experiments, all transition ions are queued one after another for measurement, which significantly decreases their throughput and limits their use to a few target proteins.1 The main drawback of the targeted strategy is that it can be applied only to the known HCPs.12,15

Data analysis and interpretation

Following the MS/MS detection step, the generated data must be processed and analyzed in order to obtain information about the identified HCPs. The acquired experimental MS2 mass spectra of peptide fragments are compared with theoretical mass spectra deposited in the database. To achieve this, software programs use special algorithms and a scoring system. Each comparison between the experimental and theoretical spectra is scored on the basis of quality match and all matches are evaluated statistically. The obtained information is used to identify the protein from which the tested peptide fragments originate. Theoretical mass spectra are predicted based on the peptide sequences from host species proteome database. Notably, the proteome databases are generated from genome sequencing, and may sometimes provide inaccurate information (e.g. resulting from open reading frames, or exclusion of different isoforms of proteins). Proteomic databases commonly used for data analysis include: UniProt, Swiss-Prot, NCBI. The chosen database should be implemented with external protein sequence, such as sequences of the desired product protein and any proteins co-expressed from vector or cell line, media proteins, process-related impurities (e.g. protein A), digestion enzymes (e.g. trypsin), or any peptide or protein added for quantitative or system suitability purposes. Additionally, ranges of some parameters in program should be defined as a searching criteria for analysis of collected data. The most important parameters of software include mass accuracy for the peptides and their fragment ions, digest specificity, and number of allowed proteolytic missed cleavages and a list of amino acids modifications.1

It is also necessary to verify the correctness of the results interpretation provided by software program. To ensure this, False Discovery Rate (FDR) is set. FDR determines the percentage of false positive results that can be accept by system. A lower value (e.g. 1%) indicate a more conservative program. The software has different ways of implementing FDR at both the peptide and protein levels. An additional tool to reduce the number of false positive results is the decoy database. The decoy database consists of non-existent protein sequences, usually created by randomizing or reversing amino acid sequences of true protein entries. They are usually automatically generated by a software during the data processing. These actions are especially important in the context of low-abundance HCPs.1

There is no unified approach for determining the minimal number of unique peptides required for positive identification of HCPs. In general, the more peptides are matched, the greater the confidence that HCP has been identified correctly. At least two unique peptides are usually required to obtain satisfactory results. However, it is possible to identify the protein using a single peptide (so called one hit wonder), especially when HCP have low abundance and are close to noise level. Nevertheless, in such cases the results must be subjected to additional verification, which usually involves manual inspection of the confirmatory peptide-level data, such as: XIC trace, MS spectrum, and MS/MS spectrum.1

Quantitative determination of Host Cell Proteins by LC-MS

In addition to protein identification, LC-MS technology also enables the quantification of individual HCPs. Unfortunately, this approach is fraught with challenges related to the differences in ionization efficiency, fragment ion generation, protein digestion efficiency, dynamic and linearity range. Because the HCPs profile in examined sample in unknown, the quantity must be determined in relation to other peptides or proteins (product or spiked internal standard). As in all multianalyte tests, the accuracy is subject to great variability.

In most LC-MS methods the intensity of signal is measured as an area under identified peak or its height at either the MS (precursor peptide ion) or MS/MS (fragment ions) levels.1 The publications present various methods for translating signal intensity into Host Cell Proteins quantity. The most common one is called Hi3 label-free quantification or Top3. It is based on assumption that the average MS signal response for the three most intense tryptic peptides per mole of protein is constant. The obtained average for the standard is used to determine the universal signal response factor, which in turn is used to calculate the concentration of the remaining proteins.20 There are three major types of relative quantitation: relative to product protein, relative to spiked-in protein and relative to spiked-in peptide. In the first strategy, the product protein is used as a relative quantitation standard and the quantity of HCPs is estimated from signal ratio between HCPs and the product protein’s peptides. This method can be applied only when the amount of product injected on column is known and the signal of product’s peptide is in working range of the instrument’s detector. The second method uses one or a few proteins as a standard. The selected proteins must generate unique peptides. The standard is added to the sample at known concentration at the beginning of sample preparation, ensuring its proteins go through the entire procedure along with HCPs. Usually, according to the Top3 method, the three peptide signals from a protein standard with the highest intensity are compared to those from each HCP, and signal ratio is calculated. The third approach uses spiked-in peptides as a calibration standard. Peptides can be added to the sample before or after the digestion step. The selected peptides can be unlabeled but unique for HCPs pool, analogously to the spike-in protein. Alternatively, they can be synthesized, and stable isotope labeled (SIL). The SIL peptides are used only in the targeted analyses, where a limited number of known HCPs is monitored. Because SIL peptides have the same retention time and fragmentation behavior as HCPs peptides, their use enhances method’s accuracy and robustness.1,14,16

Summary

The development of LC-MS/MS technology provided an opportunity to use MS-based methods as orthogonal methods for Host Cell Proteins determination. They produce more detailed information on individual HCPs, enabling both their identification and quantification. Moreover, they allow to characterize the impurity profiles and recognize the critical HCPs. This can be followed by a well-grounded risk assessment as well as building HCP removal strategy and evaluating its efficiency.

Potential limitations of each method should be taken into consideration when developing the LC-MS-based strategy. The greatest challenge in HCP identification by MS is a dynamic range limitation of MS detection. The difficulties will depend on the type and origin of the sample (HCPs abundance relative to the product). Due to the higher concentration of HCPs, upstream and downstream process intermediate samples are less problematic than highly purified samples such as drug substance, where impurities are reported at the ppm level. To overcome these limitations, enrichment or depletion strategies can be used to reduce the amount of product proteins during the sample preparation stage. However, it is important to remember that additional steps in sample preparation may carry the risk of HCPs loss and compromise quantitative accuracy of the total HCP detection.

The strategy of MS analysis and detection should be aligned with the defined purpose. Some approaches are better suited for qualitative characterization of total HCPs, while others are more appropriate for identifying and quantifying a few specific HCPs. The untargeted strategy can be used for initial characterization of the HCPs profile or to monitor its changes. The targeted approach is optimal for tracking critical HCPs in the process or during the assessment of modification implemented in the polishing process. ELISA continues to be the leading method of HCPs measurement due to its excellent sensitivity. However, considering its limitations, it is recommended to implement orthogonal assays to provide additional confirmation of the product’s quality. LC-MS can complement the results of ELISA, delivering a more comprehensive picture of protein impurities and reassuring that no significant HCPs were missed by immunoassay. Each of these methods can be used in a different context depending on the amount of data that needs to be obtained. ELISA, which reports the total concentration of HCPs is suitable for quality control release testing of drug substance and for monitoring the process development and validation. The LC-MS based method is more likely to be used during the development stage of the process, before entering the clinical phase. The characterization of Host Cell Proteins pool enables faster risk assessment, and if needed, modifying manufacturing process to reduce the negative impact of HCPs on patients’ health.

Prepared by:

Nina Trzęsicka

References

- USP General Chapter <1132.1> Residual Host Cell Protein Measurement in Biopharmaceuticals by Mass Spectrometry. United States Pharmacopeial Convention: Rockville, MD, 2024.

- Park JH, Jin JH, Ji IJ, An HJ, Kim JW, Lee GM. Proteomic analysis of host cell protein dynamics in the supernatant of Fc-fusion protein-producing CHO DG44 and DUKX-B11 cell lines in batch and fed-batch cultures. Biotechnol Bioeng. 2017;114(10):2267-2278.

- ICH Q6B specifications: test procedures and acceptance criteria for biotechnological/biological products- scientific guideline.” (1999): CPMP/ICH/365/96.

- Vanderlaan M, et al. Experience with Host Cell Protein Impurities in Biopharmaceuticals. Biotechnol. Prog. 34(4) 2018: 828–837.

- de Zafra CL, Quarmby V, Francissen K, Vanderlaan M, Zhu-Shimoni J. Host cell proteins in biotechnology-derived products: A risk assessment framework. Biotechnol Bioeng. 2015;112(11):2284-2291.

- LC-MS-based host cell protein (HCP) identification and monitoring during biopharmaceutical downstream process development, Xiaoxi Zhang, Zijuan Chen, Bingnan Li, Jennifer Sutton, Min Du, APPLICATION NOTE 74162, Thermo Fisher Scientific.

- Guideline on development, production, characterization and specification for monoclonal antibodies and related products, EMA/CHMP/BWP/532517/2008, 21 July 2016.

- Bracewell DG, Francis R, Smales CM. The future of host cell protein (HCP) identification during process development and manufacturing linked to a risk-based management for their control. Biotechnol Bioeng. 2015;112(9):1727-1737.

- Champion K, Madden H, Dougherty J, et al. Defining your product profile and maintaining control over it, part 2: challenges of monitoring host cell protein impurities. BioProcess International 2005;3:52-7.

- Zhu-Shimoni J, Yu C, Nishihara J, et al. Host cell protein testing by ELISAs and the use of orthogonal methods. Biotechnol Bioeng. 2014;111(12):2367-2379.

- <1132> Residual Host Cell Protein Measurement in Biopharmaceuticals.

- Walker DE, Yang F, Carver J, Joe K, Michels DA, Yu XC. A modular and adaptive mass spectrometry-based platform for support of bioprocess development toward optimal host cell protein clearance. MAbs. 2017;9(4):654-663.

- Mortz E, Kofoed T. Regulatory Consequences of New Protein-Impurity Guidelines. BioProcess International, 2024.

- Pilely K, Johansen MR, Lund RR, et al. Monitoring process-related impurities in biologics-host cell protein analysis. Anal Bioanal Chem. 2022;414(2):747-758.

- Huang Q, Yang L, Luo J, et al. SWATH enables precise label-free quantification on proteome scale. Proteomics. 2015;15(7):1215-1223.

- Heissel S, Bunkenborg J, Kristiansen MP, et al. Evaluation of spectral libraries and sample preparation for DIA-LC-MS analysis of host cell proteins: A case study of a bacterially expressed recombinant biopharmaceutical protein. Protein Expr Purif. 2018;147:69-77.

- Huang L, Wang N, Mitchell CE, Brownlee T, Maple SR, De Felippis MR. A novel sample preparation for shotgun proteomics characterization of HCPs in antibodies, Anal. Chem. 2017;89(10):5436–5444.

- E SY, Hu Y, Molden R, Qiu H, Li N. Identification and Quantification of a Problematic Host Cell Protein to Support Therapeutic Protein Development. J Pharm Sci. 2023;112(3):673-679.

- Improved data quality using variable Q1 window widths in SWATH acquisition, Application Note, SCIEX, 2019.

- Silva JC, Gorenstein MV, Li GZ, Vissers JP, Geromanos SJ. Absolute quantification of proteins by LCMSE: a virtue of parallel MS acquisition. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2006;5(1):144-156.

Related resources

UV-VIS Spectrometry for Protein Concentration Analysis: Principles and Applications

Analytics, Biologics, Proteins

Does Your CDMO Have An Analytical Edge?

Analytics, Biosimilars, Mabion

Innovative biologics – expected drug approvals in 2025

Antibody-drug conjugates, Biologics, Bispecific antibody, Clinical trials, EMA, FDA, Monoclonal antibody, Vaccines